Imaginative play helps me hold on to hope, even in the most horrible of circumstances. I’m currently in the midst of some challenging and transitional days in my professional work as a Lutheran minister, not to mention the latent dread about what this new and chaotic administration will bring to the United States. Perhaps it’s these things that are bringing me back to my conversation with some folks at Australian Broadcasting Corporation (basically Australian public radio) from last fall when I got to talk with Rohan Salmond on Soul Search about my work with TTRPGs. Give it a listen!

**************

ML: Hello, Meredith Lake here. Want to play a game? I mean, Soul Search is a show curious about important and serious things: spirituality, religion, the contemporary search for meaning. But what if games and playing games can be a path to meaning? Rohan Salmond is the producer of this humble show. Hi Rohan, what do you reckon? Can playing games help us find ourselves?

RS: Hi Meredith, I have a feeling that they might help.

ML: Is this because you play a lot of games yourself?

RS: I do. I love board games and computer games. I’ve been playing them for a long time, Meredith.

ML: You don’t have to admit to anything, but you are very online. I’m not averse to a bit of a board game myself, but it’s interesting to think about how games can be about more than having fun. Because, I mean, you don’t have to think about it for long to realize that, oh, actually, a lot can be going on when we play a game. Kind of the quest for meaning being something that happens when we play a game. I mean, how is that something that came up for you?

RS: Well, a couple of weeks ago, when we were talking to Rod Pattenden, the artist, about imagination, I was really interested in what he said about the role that imagination has in creativity. And I’ve had the experience of playing, you know, tabletop role playing games, these sort of games of make believe that have rules around them that determine, you know, whether or not you’re actually able to do something. It’s engaging that same sort of area of creativity, but it also says something about the person, or at least, I suspect that it says something about the person who’s, you know, made and is inhabiting that character.

ML: So I mean, a famous example of a game like this might be something like Dungeons and Dragons, right, where you know you have dice and you have rules, but you also invent your own character, and then in that persona, navigate the game and its challenges and interact with other people’s characters. That’s the kind of tabletop imagination game that you’re talking about.

RS: Yeah, and there’s a guy who I came across online while I was researching a completely different show. His name is Pastor Rory Philstrom, and he goes by the “Dungeon Master Pastor” online.

ML: Okay, have to say this isn’t something that I’ve come across, perhaps because I’m not very online. But what’s the “Dungeon Master” part?

RS: So he is the person who runs the games. So he doesn’t often play a character himself, but he writes the world and provides the challenges…

ML: He’s like God?

RS: Kind of, yes.

ML: Haha, hmm okay. I hope you ask him about that, Rohan.

RS: Yeah. Well, I was, I was really curious to get his take on this, about this suspicion that I have about what’s happening when you actually write a character and play it out on the tableto.

ML: And what that could possibly mean, perhaps for the way we search for meaning and figure out our spirituality, our religion, all those kind of things? Rowan, thank you. I can’t wait to hear this!

RS: Thanks.

RP: I’m Pastor Rory Philstrom, and I am the lead pastor at my Lutheran congregation here in Bloomington, Minnesota, and I’m also the Dungeon Master Pastor for a project I call Roll for Joy, where we adventure using tabletop role playing games in order to discern hope and find ourselves and have fun.

RS: So Rory is a Christian pastor and a big time game player, but let’s wind back to the beginning. How did he fall in love with these games of imagination?

RP: Yeah, I started as a kid. My grandma bought me a black box with dragons on it, and it was an intro to Dungeons and Dragons. I made my sister play it with me, though she quickly stopped, and I had to sort of run it through myself. Then I would bring it to, this is in elementary school, I’d bring it to the latchkey after school program, and make my friends go through the dungeon so that I’d have somebody to play with. And then I stopped playing for a long time and got back into it when I was serving as a pastor in western North Dakota, which is kind of like barren, ranching, not a lot of people. I was with a group of pastors hanging out, and one of them said that they had heard about this game, Dungeons and Dragons via a podcast, and they had to play. They had to experience what it was like. And I sort of sheepishly said, “I know how to play.”

RS: “I know all about that.”

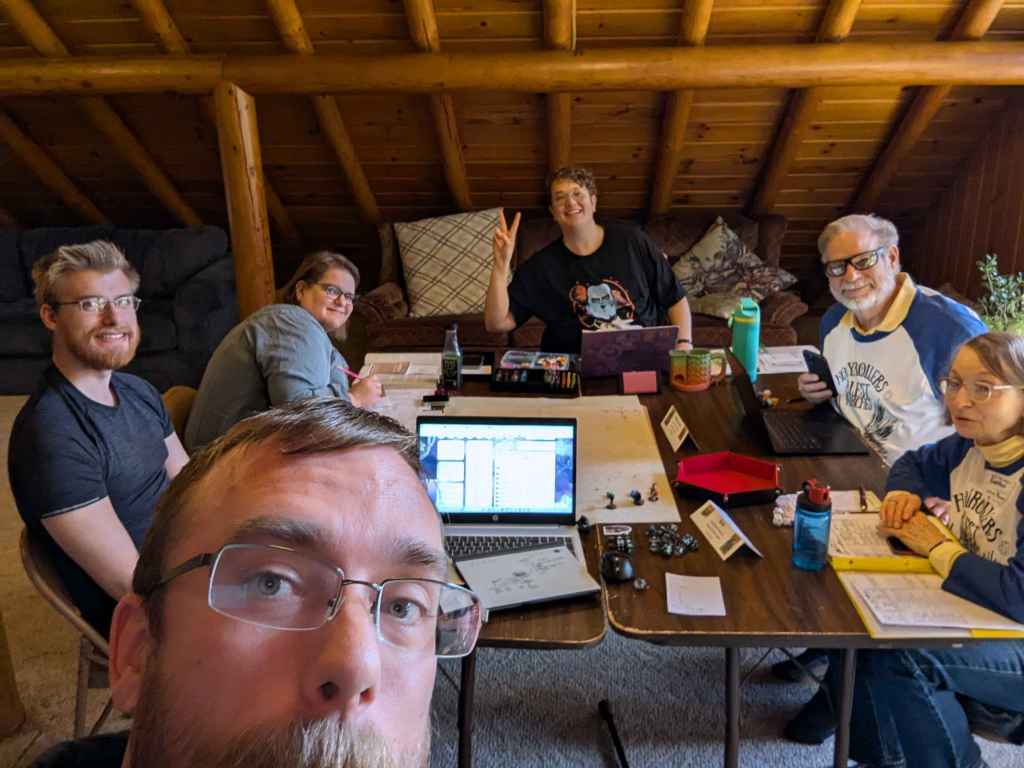

RP: Yeah. And was back in it. And pretty soon we had, I think there was near nearly a dozen clergy from across the state of North Dakota who were gathering together online once a week to be together with people that we all sort of understood our lives as pastors, but also could set that aside and just be people and play.

RS: Yeah, that’s so interesting that you got back into it, that all the other players were clergy, because, of course, you know, there was the Satanic Panic around Dungeons and Dragons, and it hasn’t always been very well received in Christian communities.

RP: Yeah, so I run a I run a retreat where I invite ministry leaders to come and spend four days playing Dungeons and Dragons and talking about ministry. I’ve done that since 2018. And at our last retreat last year, we had Derek White, Pastor Derek White, who also goes by the moniker the Geek Preacher. And he’s actually produced a documentary talking about that Satanic Panic, and it goes through the experiences that he had as a kid, where his parents burned his D&D books.

I had never had that experience. You know, I’m younger, so I grew up more in the in the 90s and in early aughts than in the 80s, when the Satanic Panic was really big. Acts of the imagination, reading fantasy… it was not seen as a threat.

RS: Yeah, you’ve used games like this as a ministry tool, it sounds like for for quite some time. What is the draw to using this tool in particular?

RP: Yeah, I use it… one, because it’s, it’s something that I have found, personally, very rewarding and sort of unlocking, freeing perhaps. It’s something that has unlocked in me creativity in all sorts of ways. And it’s a medium, a tool, that can sort of take any kind of creative impulse that you might have, whether it’s storytelling or art or writing or, you know, music – in playing a game where you’re imagining an entire world and the people in it, there’s room for all of that. And it just is a great big space to play in, and I’ve found that to be personally freeing. And so I I have leaned into my joy in that and shared that with others.

And not, I mean, not everybody is into it. It’s not a game for everybody, but for those that get over the feeling of, “Okay, we’re playing make believe again, and we’re not little kids,” and are okay with that, once you get over that sort of barrier, people get to that place of freedom.

And I think, as a person of faith, that’s at the core of what I believe – in my faith in Jesus that’s the message. It’s the message of salvation, which is freedom, which is liberation, which is being free to live into the fullness of who you are and who God has made you to be. And there are ways that the game can unlock parts of ourselves that a lot of times we keep hidden away.

RS: I’d love to explore with you what you think is happening when somebody makes a character. What are they really doing through that process?

RP: Yeah, when somebody makes a character, they are saying, “This is a part of myself that I want to play with. This is a part of myself that I want to become, just for a little bit in this game of pretend.” And, you know, they’re deciding, “What is this going to be that’s fun?”

That’s, I think, what people do when they create a character on the surface. And underneath the surface, if you just start to scratch at that, you begin to see through reflection that this character is saying something about either who this player wants to become, or who this player is afraid of becoming.

We can, and people have used games and use that play to create characters that just rehash the problematic aspects of the world. I think there’s freedom in it, but it’s a tool, and it can be used for ends that are positive and for ends that are negative.

RS: What sort of problematic tropes are you talking about?

RP: Sure, I mean, there’s problematic tropes around characters that are racist, characters that just like, write off, like, “I’m gonna play an elf and I’m just gonna write off all other people that are dwarves,” and “I’m just gonna play racism,” you know. So there’s problems there.

Or there’s problems that were actually written into earlier versions of the game. Like, if you were to play a female character, a female hero, your ability scores were capped. They were less than they could be if you were male. And there was this sort of bio essentialism around your capacities.

Another way it shows up is in religion and games. A lot of times, in a fantasy world, in the fantasy stories that are made the evils of the world are laid at the feet of the gods. Stories get told then of religious warfare, where you are slaughtering the religious ‘other’ just because they are ‘other.’ And you’re not thinking or discerning or, like, making any attempt to determine if the creatures that you’re killing in the game are actually, like, really on board with the thing, or if they’ve just been roped in.

And so there’s ways of world building that that you can use to get away from that.

RS: To deconstruct that a little bit maybe?

RP: To deconstruct those things where you are defining, “Well, this kind of ideal, this kind of thing is good, and this is bad.” And clearly the heroes then, are pushed to slaughter the bad things, which is really just an impulse that has not served humanity all that well.

RS: That sort of thing requires a responsible Game Master, I think, to ensure that intentional play happens, because it’s so easy to replicate and not question the things that we’ve received from the culture around us.

RP: It is. Yeah, it takes, it takes a bit of skill and just awareness of that as an issue. And I think once you kind of figure that out, that yeah, there are other stories, better stories that we could tell, more interesting stories that we can tell together.

But yeah, you talk about empathy. I think in the game, whether you are a player or a dungeon master, just that act of like, trying to imagine yourself in the shoes of another person in another experience – it really like exercises that muscle and makes you really consider, “Okay, what’s the world like for somebody else who isn’t me?”

That is a muscle that can atrophy. And I’ve seen it atrophy here in the United States a lot, when we don’t play with it. But we operate based on prejudices, judgments about people that are, you know, preconceived because it’s easier that way. It’s easier if, you know, we are to think that “black people are violent criminals”. And it’s why, unfortunately, we’ve seen so many problems with police shootings, especially of people in black and brown bodies, here in the United States and here in in my city of Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed and murdered, where My wife’s high school classmate Philando Castile was killed at a traffic stop. You know, there’s just an epidemic of these things and a real lack of the ability to imagine people in a complex way.

****************

RS: It’s Rohan Salmond here on Soul Search, and I’m talking with Rory Philstrom. Rory is a Lutheran minister in Minnesota who is also known as the Dungeon Master Pastor. He spends a lot of time playing games, often as part of his Christian ministry, and that’s because he sees games of imagination as a way of building empathy in the people who play them.

This episode of Soul search is all about the connections between games imagination and how some people find a sense of self and a sense of meaning in the world. And so back to Rory. I want to hear more about the last game of Dungeons and Dragons he played. What kind of characters did people make for themselves and what happened?

RP: The last game of Dungeons and Dragons that I played was actually just a couple nights ago at a Bishop’s Theological Conference with a bunch of pastors. So the first thing that we did as part of the game was create characters together.

And so, when you build a character in a tabletop role playing game like Dungeons and Dragons, even if you don’t mean to you are putting a bit of yourself into the story of this character. And some people do that intentionally, kind of playing as their aspirational self, you know, the person that they really want to be. Some of them play more moderately as themselves, and just kind of like bump up their abilities a little bit. And some people play as their shadow selves, you know, in some ways, consciously or unconsciously, they explore something about themselves that they usually don’t bring to full consciousness.

Once characters are created, they’ve created a little bit of a back story. And then once you start playing. Once a player tries to live into that character – the plan that they had made about that character – once it meets reality, once it meets the challenges of the adventure, it doesn’t always survive. There’s that saying, “No plan survives the encounter with the enemy.” And no character concept survives interacting with anybody else.

RS: So the other players too, yes, right?

RP: And the other players! So they’re like, oh, you know, maybe they bond with somebody, and they’re drawn out because of something they see in another character. Or maybe they have a strong reaction to another character. Or maybe there’s some tension, or some some dynamics there, and they have to figure out, ultimately, how are we a community together? And in that, I think, continue that process of discovering who they are.

There’s a South African concept of ubuntu – “I am, because we are.” I believe that in that play, in that process of meeting the other characters and interacting together, they are still doing that same work that I was talking about during character creation – of becoming who they are through those interactions and in a space that is safe in a way.

You know, there’s some narrative distance between me as Rory and Kitiara, my character who I might play in a game. I can pretend to be her and interact in some ways that I might not feel comfortable doing in my own day to day life or social interactions. You can play with these concepts and kind of explore together in a way that’s guarded or protected, and doesn’t have a lot of consequences for my day to day life if I don’t want it. And so it’s a great like laboratory for discovery.

RS: Hmm, I wonder if there are parallels there as well, with people coming together as a community in in a church context too, that encountering other people and learning about yourself and each other?

RP: I think it’s really interesting to think about. And it’s been interesting, you know, as a pastor and as a dungeon master, to be convening people in what are really very different spaces, and yet also spaces that have a lot of similarities.

And you know, some of the similarities I think about… like leading worship. When I lead worship, what we’re doing is inviting people into this sort of sacred space and time, apart from the day-to-day patterns of the world. In that space and time, people are, you know, we act differently. There’s different rituals that we share. A meal where everybody is served the same amount, no matter how much they have in their bank account. We have a practice of, you know, passing the peace, where we greet one another, even people that we might not know very well or like very much on the surface, we still offer a greeting of peace. And we, you know, practice setting aside our grudges, setting aside our vindictiveness or our vengeance or judgmentalism, and seeing each other with more open eyes. And then we go back to the world.

In the same way, you know, when I bring people around the table, they come and they can kind of set aside their daily life, and they interact in different ways, gathered around different values. They band together and do heroic things, courageous things, confronting enormous evils. And they never really lose sight of the hope that that they can succeed, that they trust in the game, that there is a happy ending at the end of it, and that each person in the group has a part to play.

But I think there’s… the thing that’s different, is that when you go to a to a church, when you go to a congregation, a lot of times there is – and it hurts my heart to say this – but there’s, for a lot of people, a lack of safety in those spaces. When you go, you have to put on a mask, because you’re afraid that, “If people knew the real me, they wouldn’t allow me in here.” I don’t know how many times I’ve heard people say to me as a pastor, like, “Oh, I walked into your church for this funeral, and you’re lucky that the building didn’t burn down,” because that’s the impression that they have, that “I am so bad and not good enough to be here.”

And so when people come a lot of times, they come with this guard up. That it’s hard to be yourself. And I think in the best Christian communities and the best faith communities, there is enough safety built that people will eventually be able to let their guards down and be just human people that are caring and loving and community together. But in a church context, it’s really hard to be that, especially if you’re a LGBTQ person, or if you’re walking into a church and you’re a minority of the demographic that that church traditionally serves. There’s some guards up.

RS: Has running games helped you think about ways that you could make your own community a safer place?

RP: Yeah, I think there is a way that it is easier when you run a game, because it is so much smaller. You know, the game is naturally limited to the number of people you can fit around a table. And with that number of people you can be very explicit about ways that you can keep each other safe, and the ways that you encourage belonging, and the ways that you can be people together.

Whereas, at the scale of a congregation, where you might have 100 people in a room together, it can be a lot harder to do that. But I think there is value in being explicit about the values commitments to one another for a congregation to have.

In our congregation in this last year, after a series of conversations, we became a Reconciling in Christ congregation, which is a term used in our denomination to say that we have an explicit and published message of welcome for people of any gender expression, gender identity, any racial background or ethnicity, that says, “No matter who you are or how you are in this life, we welcome you and you are sacred here.” And just saying that you know, says something about the community there that can allow people to start to feel some of that safety and like they might be able to belong. But then you have to also do the work. You can’t just have a statement. You have to, you know, have that influence the way that people are together.

RS: On Soul Serarch, on Radio National and ABC Listen, you’re with me, Rowan Salmond and I’m speaking with Dungeon Master Pastor Rory Philstrom. He’s the lead pastor of a Lutheran Church in Bloomington, Minnesota, and he also runs tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons and Dragons, which he says is a way for people to explore who they are, have fun, and pursue joy. So tell me more about that, Rory. These are games where people take on a character and confront challenges in an elaborate, imaginary setting that you’ve written actually. So what kind of worlds do you make for your players?

RP: Hmm, I… a lot of times the worlds and the adventures and that I set up are going to be hard. There’s going to be something that makes people uncomfortable, or, pushes them to their limits. The challenges are going to be steep, and the stories are going to be big. And I don’t do that to like, savage my players or anything like that, but so that the stories that they tell are about them overcoming enormous challenges.

So I mentioned I run a retreat, and the world that we play in is a world that I created for that first group of pastors that played together. And in that world, where we were all pastors and all very familiar with religious stuff, the first thing I told people was, “Okay, we can play this game, but none of you can be religious people. No clerics, no paladins. There’s no gods in this world right now. We’ll have an adventure to see if you can figure out why there’s no gods in this world and what’s going on.” But that was where we started, a bunch of religious people playing in a world without religion so that we could, you know, really set that aside and lean into other aspects of who we were.

RS: And what do people learn about themselves by playing in these kinds of environments?

RP: Oh, I think, I think they learn that they can do hard things. I like to think so anyway. I think no matter how big the challenge is that there’s always hope, and that that holding on to hope is just so vital. It’s vital to keeping the story moving forward in our journey. If the characters who are supposed to be the heroes get scared and hide under a rock and don’t engage… then the story ends, and we stop having fun, and we all go home.

But if they hope that even though the world has just cracked open and this elder abomination has descended and everything is going wrong, that they can still do something about it… that now, you know, they still try. And in the game, the fun of the game is putting challenges in front of players that they don’t know that they can overcome, but if they work together they do.

And there is that promise that you can, and that’s important in our lives as well. And I think a really important lesson for me has been that my son -who is about to turn six years old, he’s going to turn six next week – five days after he was born, we received a call that he was diagnosed on our newborn screening with a disease called Spinal Muscular Atrophy, which is a devastating illness and one that was one of the largest causes of infant mortality before there was a treatment available. It’s actually a lot more common than you might think.

So untreated his life expectancy, his story, was largely written. If he had the most common type of the disease, he wouldn’t have lived past two, the odds were. It’s a muscle degenerative disease where his muscles degrade. And if he has the ability to crawl, he loses it. If he has ability to walk, he loses it. Then just slowly, eventually loses the ability to breathe.

You know, facing that was enormous. This huge, horrible thing. And he was the fourth kid in our state ever screened for it, and the treatments were still new, still experimental. And you know that what got me through it was living in hope each day, that this experimental treatment was going to work. That there was something that that could be done and that we could still live into a full story of a son and a father. That that he could have a full life, no matter how much there was of it.

And so, holding on to hope in the face of enormous challenges was something that took on a real life meaning for me. That was a skill that I practiced running games where I put huge challenges in front of people and told them, “You can do this!”

RS: But also a such a important part of Christian faith too.

RP: Yeah, incredibly important. And I think really speaks to, you know, that hope in the Christian faith is not in something that you can see. It’s a hope in things unseen. And it’s a hope that even in the worst possible circumstances, which is summed up by Jesus on the cross, that there is something that God can do with that. I’m not a person that takes to the idea that God causes these things to happen. I think humanity carries a lot of that blame – just in our own freedom and limited ability to see the impact of our actions and the fullness of that – but that, you know, in the messes we create… God can still make something of them.

RS: Thank you, Rory for sharing that.

RP: Yeah, it’s… by no means was it or has it been the only hard time. You know, being a person of faith doesn’t mean that things go easy. But it means that you still trust that things go, even if they’re not easy.

RS: Just to conclude, even if you don’t play these games regularly, if one finds it too hard to, you know, understand the rules, or maybe even, you know, find other people to play with, I wonder… what’s a practice or idea that anyone could take away from what you’ve learned playing these games?

RP: Sure. What’s coming to mind is there’s a theologian, Jürgen Moltmann, who is probably my favorite theologian. He was a German guy. He actually just died this past summer in his 90s. But he was German and a youth in the era of World War II. He was conscripted in the Nazi army and fought as a Nazi in World War II, before surrendering to the allies. And in a reeducation camp, he came to faith. He studied theology and became a scholar, and really did that through wrestling with the ugliness of the world. Through wrestling with that, he found faith and found God and found a way of being that could move him beyond that. And one of the things he writes in a book called Theology & Joy, is about using the imagination, and the importance of using spiritual imagination, and the power of our imaginations and of our play.

And he talks about play as powerful. Not when we play with the past in order to get to know it. It’s not about playing with what is, but the power of play is in productive imagination and playing with the future in order to get to know it. And so I think, whether you play with that future in the space of a roleplaying game like Dungeons and Dragons, or play with that future in whatever creative endeavor you want – whether that’s poetry or storytelling or music or whatever. However you play, play offers us a space of freedom to figure out what might be, what could be, and as we play into it, what we can learn to become.

RS: Thank you, Rory, for sharing that with me. It’s been a real joy to talk to you about this, and so interesting to see the ministry played out in such a different way. Thank you so much.

************

RS: That’s Pastor Rory Philstrom, the minister of a Lutheran Church in Minnesota, and also the founder of Roll for Joy, a gaming ministry big on bringing the joy of play to the rest of life as a way of finding freedom.

ML: Hey, Rowan, thank you. Thanks for introducing me to Rory. As you know, I’m not much of a game player myself. I’ve never played Dungeons and Dragons. But you know, what he said about hope especially, really resonated with me, just because, you know, hope can be so hard won in the circumstances of our lives. And I loved, you know what he was saying about how it can be practiced, like empathy, like a muscle that we can build with use. Yeah, I found that really a beautiful thing to think about, actually.

RS: Yeah, I think that we could all do with, you know, a bit more hope in our lives. And, like, it’s kind of funny you think about play and how children use, well, “use play+” is maybe not the best phrasing, but you know, they are practicing things that that they go on to use, and I don’t see why that should stop in adulthood.

ML: Yeah. I mean, it’s a key way of making sense of the world and your own play… your own place. Funny, slip of the tongue there, yeah. And I guess that’s partly why imagination games have become so important to Rory, even in his work as a Christian pastor. It makes sense for at least some people for there to be a huge crossover right there.

Leave a comment